Development of the city’s drainage

Dundee’s drainage system has a long and complex history. Dundee was built on a ridge overlooking the River Tay, the steep slope meant that surface water runoff was relatively easy to manage. However, as the town grew and expanded into the surrounding valleys, it became necessary to develop more formal drainage systems. By the 17th century, some streets had rudimentary drains, but most of the town’s sewage and surface water runoff still flowed directly into the Tay.

Early 19th Century

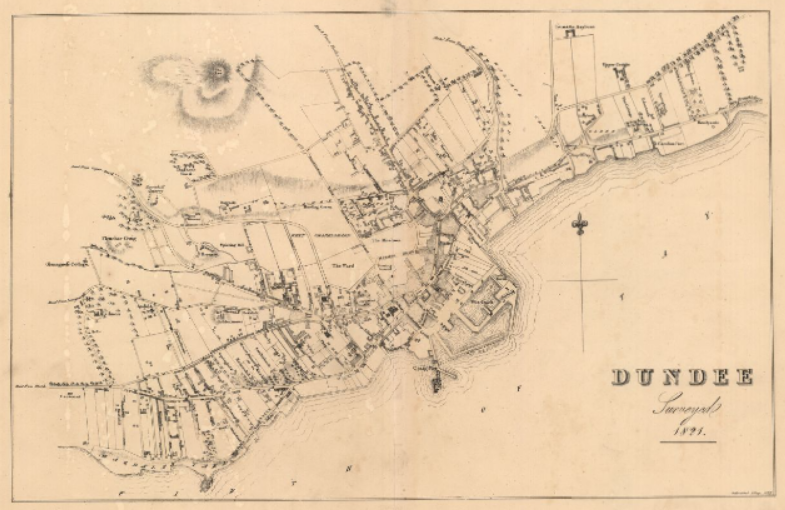

Map of Dundee 1821 Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland (https://maps.nls.uk/view/74400021)

It wasn’t until 1824 that Dundee Police Commissioners were appointed with responsibility for lighting, paving and cleansing of the town. The Commissioners appear to have been largely ineffective in delivering great changes until being supplemented with Health and Sanitary inspectors in the 1850s and 60s. Dundee saw huge growth during the 19th Century largely down to its Jute manufacturing. From 1850-1900 the population doubled in size to 160,000 fuelled by its industrial boom. It was the Dundee Improvement Act of 1871 that really moved things forward for the town, enabling new streets (such as Victoria Road, Whitehall Street and Union Street) to be built and redeveloped. The Act also gave the Police Commissioners the power to move forward with a bold project to drain the Burgh of Dundee and the outlying and rapidly expanding area of Lochee. By the end of the 19th century, Dundee had a relatively comprehensive sewerage network, although it still relied heavily on the river for disposal of wastewater.

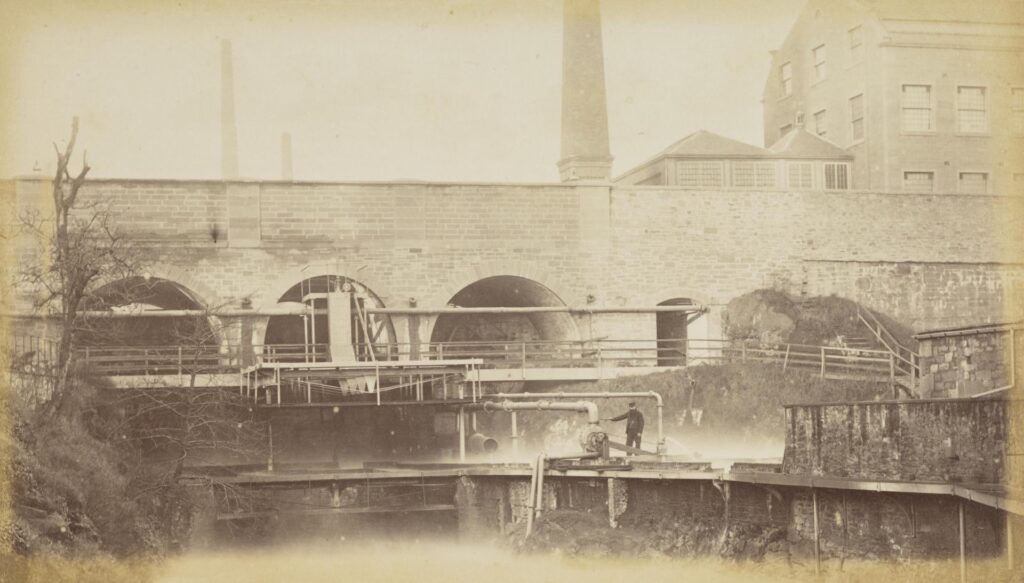

Victoria Bridge, South Side, as seen from Dens Works. James Valentine 1871-1880. National Galleries of Scotland.

The Lochee Sewer was the first phase to be constructed, using John Frederick La Trobe Bateman’s prowess for hydraulic engineering, the route follows a contour around Menzieshill (south of Ninewells Hospital these days) and onto Perth Road, leading to the Nethergate and High Street. This work was completed in 1880 but ultimately compounded a flooding risk in the Seagate area of the town centre.

Early 20th Century

Dundee saw continued growth and expansion with milling, weaving and heavy industry still centred around the old watercourses and expanding drainage system. Despite Bateman’s scheme, there were still 37 outfalls discharging sewage and effluent to the Tay, many of which were pipes though sea walls, into the harbour docks or on to recreational areas such as Grassy Beach or Broughty Ferry.

Late 20th Century

With the Tay Estuary having a huge tidal exchange and capacity for dilution and dispersion, the concept of natural “treatment” in the environment prevailed for decades, as it did in other coastal cities around the UK and the world. However, in the 1970’s European legislation such as the Bathing Water Directive of 1976 started to move EU member states towards a common standard of environmental performance and a drive to improve public health.

In the late 1990’s, in a similar fashion to the Dundee Police Commissioners, North of Scotland Water Authority invited experienced engineers to come up with a solution for Dundee’s drainage and treatment requirements utilising a different funding route (i.e. PFI). Using modern network and marine modelling techniques, a regional scheme was developed that sought to improve water quality in the Tay Estuary, to enable continued growth of the city and to deal with by-products of treatment processes in a sustainable way.

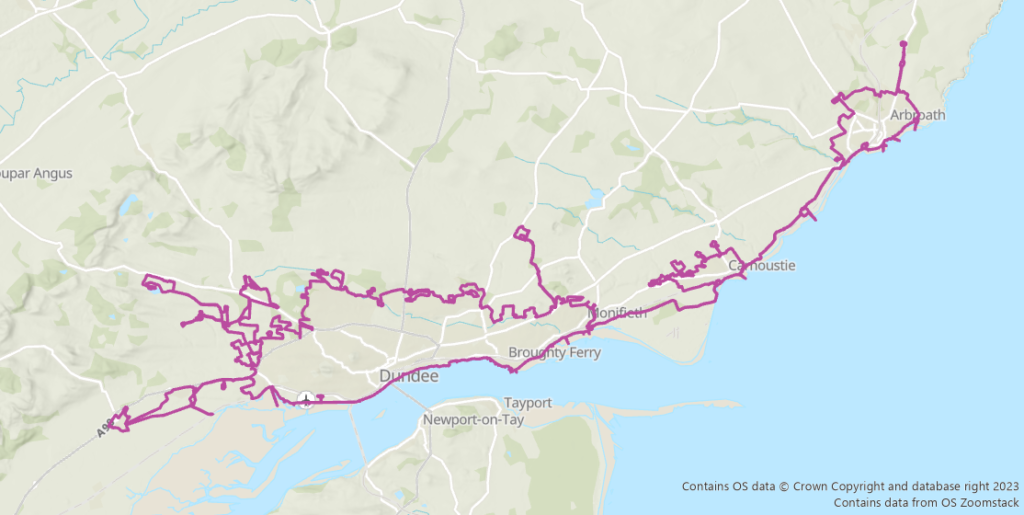

In 1999, a contract was awarded to Catchment Tay Ltd to design, build and operate a system of pumping stations, tanks, pipelines and a single treatment works for a duration of 30yrs. In 2000, what was the largest civil engineering project in Scotland at that time saw the construction of 35km of pipelines, 7 major pumping stations and a wastewater and sludge processing centre located on a derelict World War 2 airstrip at Hatton, between Carnoustie and Arbroath at a cost of around £100m.

Hatton Drainage Operational Area

Early 21st Century

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the need for more sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) to manage surface water runoff. All new developments and redevelopment across the City must incorporate SuDS, which represents a shift towards more sustainable and effective drainage management practices.

Douglas Community Park SuDS, a multifunctional space in the heart of Douglas, Dundee.